First, what is a tax haven? This question alone is complicated, as the definition varies according to international organizations. According to the OECD: it is a country, a territory, a sector of activity or a limited territory (such as a port or an airport) that offers a very low or even non-existent tax rate. As well as a lack of transparency about the tax system, in a consciously organized market. This definition alone calls into question the classic vision of a tax haven as an island state where all the companies go. For example, France is a tax haven for Qatar because it offers tax breaks in the property sector. Another example: in almost all coastal countries, such as France or even North Korea, there are free ports where anyone can store goods without paying a single tax. These two examples already show that states make arrangements between themselves, but also with their own levies. But a new question arises: Why? Why are some countries offering tax breaks, or even not imposing any tax at all?

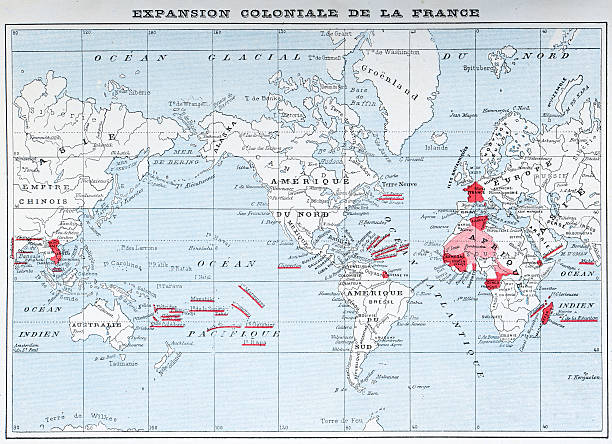

To begin with, methods of paying less tax have existed since the existence of taxation. However, the real origins of tax havens, as they are known today, came with liberalism in the middle of the 19th century. This economic doctrine, which encouraged free trade between countries, gave rise to numerous treaties to facilitate free trade, as well as tax relief in the colonies of European countries. In practical terms, to encourage companies to invest in their colonies, governments provided subsidies, loan facilities, tax relief, etc, for all initiatives to set up business outside metropolitan France. The first multinational companies therefore set up infrastructures to extract more resources, or even their headquarters in the colonies. But at the time, offering aid to companies was not a problem. Indeed, all the State had to do so to meet its budget was to tax the colonized peoples more. These are what can be considered the very first tax havens, colonies managed by states that offer all kinds of advantages to encourage settlements and investments in the name of economic liberalism.

Tax evasion really began to be debated between the wars. Certain countries such as Switzerland began to offer low taxes to companies that came to set up their headquarters there. The problem was linked to the principle that a company is subject to the taxation and rules of the country from which it is run. Therefore, in a Europe devastated by war, governments needed this income. Major debates were held at the League of Nations to establish common rules. However, no agreement was reached because countries like Switzerland blocked all negotiations.

A new turning point came with decolonisation in the 1950s and 60s. The big companies that had invested their capital in the colonies no longer wanted to leave it there. However, repatriating them to the mainland would mean paying very high taxes. So, they sent them to overseas territories, especially those in the Caribbean, because they were in the same time zone as the Wall Street stock market. Here, they would do business with corrupt semi-colonial authorities and negotiate tax breaks. However, governments could very well intervene and put a stop to these companies or these semi-colonial authorities. Why didn’t they? They didn’t because the 1960s were also the start of neoliberalism. This neoliberalism favored free trade, the free movement of capital and goods, and the privatization of the public sector, so it was not in the spirit of the times to restrain companies – quite the contrary. This was going to lead to an explosion of debt and repeated crises. What’s more, governments themselves are going to play into this environment. This is how, in part, EDF will be financed by offshore markets, how the CIA will use the opacity of tax havens to finance mercenaries around the world, etc.

What we need to remember from all this is that at no time, in history or today, states lost control. On the contrary, the liberalism of the 19th century, and the neo-liberalism that began in the 1960s, is framed and organized by the state. It is the state that signs the free trade agreements. It is the State that authorizes and promotes the free movement of capital (creation of the WTO, the EU, etc.). It is the State that has allowed relocation to take place. It is the State that adjusts customs tariffs. It is the State that plays with its own tax system, through its free ports. And conversely, it is the State that can close or limit the free movement of capital and goods. It is the State that can increase tax on profits (which is 5 points below the OECD average in France). It is the State that can organize reindustrialisation.

Finally, tax evasion, the creation of tax havens, are not excesses of modern capitalism, they are capitalism. The sole aim of capitalism is to boost profits so that it can invest more and produce more. By setting up their headquarters in countries with very low taxes, by hiding their money in countries with banking secrecy, companies are in fact simply playing the game of capitalism, they are simply using the tools available to them. Tax havens are the norm.

The 1001 lists of tax havens are just a means of distracting attention. Somehow, everyone is someone’s tax haven (France and Qatar, North Korea, and its free ports).

1 comment

Nice post. I learn something totally new and challenging on websites